Day 7: The Discipline of Seeing

Oct 12, 2025

I had a koi pond in my backyard when I lived in Frisco. Every morning I'd check the daylilies. I wanted to catch one opening—to see the exact moment transformation happened. Never did. I'd look away to answer my phone or pour more coffee, and when I turned back, the lily had bloomed. The world moved slower than my noticing.

That was a lesson in what Thoreau called the discipline of observation. The word "discipline" matters. He didn't mean discipline as punishment—he meant it as practice. A daily training of attention. Most of us think seeing is passive. You open your eyes and the world appears. Thoreau knew better. Seeing is moral work. It requires patience most people won't invest.

At West Point, they'd bark "Attention to detail, people." Back then it felt like a command. Now I understand it as philosophy. The precision of your vision determines the precision of your instruction. If you see things generally, you'll teach them generally. If you see through smoke to find the source of the fire, you can solve problems others miss. But that kind of seeing doesn't happen by accident. You train for it.

What You're Ready to Receive

Thoreau wrote in his journal: "It is not what you look at that matters, but what you see."

I used to read that line as poetry. Now I hear it as instruction. We see according to our readiness—intellectually, emotionally, morally. What we miss is often what we're not prepared to understand. A novice coach watches a player and sees motion. An expert sees the pattern underneath the motion. Same court. Different perception.

Years ago I ran an exercise with my coaching staff at Samuell Grand and Fretz. Everyone watched the same player for five minutes, then wrote down what they saw. The observations were completely different. Some focused on technique, others on body language, still others on patterns I hadn't noticed. You'd think they'd watched different players.

That's the paradox of observation. We think we're capturing reality. We're actually revealing ourselves—what we're trained to notice, what we care about, what we're developmentally ready to perceive.

When you're young, your eyes are wide but your perception is narrow. You see motion without meaning. Experience adds texture. It gives you context, depth of field, the ability to recognize patterns across time. But here's where it gets dangerous: expertise can also blind you. The more you know, the more you assume. You stop seeing what's actually there and start seeing what you expect.

The discipline of observation is the daily work of stripping away assumption. It's unlearning that keeps perception alive.

The Moment I Didn't See

I learned this the hard way during a staff meeting. I was running both Samuell Grand and Fretz tennis centers. We had a system for tracking player development—elegant, efficient, exactly what we needed. Or so I thought.

Five minutes into my explanation, I noticed nothing. Kim Kurth pulled me aside after. "Did you see them glaze over?"

I hadn't. What felt elementary to me was beyond their grasp. I'd been so deep in my own clarity I mistook it for universal understanding. My perception had outpaced my awareness of others' readiness. I was teaching from the wrong scale.

That's vision without empathy. A kind of blindness disguised as insight.

It happens in group discussions too. I'll make a connection between ideas others haven't noticed yet—links that seem obvious to me but foreign to the room. They're politely pushed past. It's frustrating. But I understand why. Seeing deeply is lonely work. Thoreau lived that loneliness in Concord. Most people, he said, lead lives of quiet desperation because they're content with surfaces. Specificity takes courage.

Growth Needs Space

I have two spider plants my niece gave me for her wedding. Small offshoots in tiny pots. A year later, they've outgrown their containers. Roots press against the edges. They need repotting. Simple observation, but it requires attention beyond care. It's recognition of constraint.

The spider plants, the glazed eyes, the koi lilies—they're all variations of the same principle. Growth needs space. Development requires proportion. The observer's job is to notice when the vessel no longer fits the life inside it.

That's what Thoreau meant about reawakening. "We must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake," he wrote, "not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn."

He's describing the Learning Zone.

The Learning Zone Model

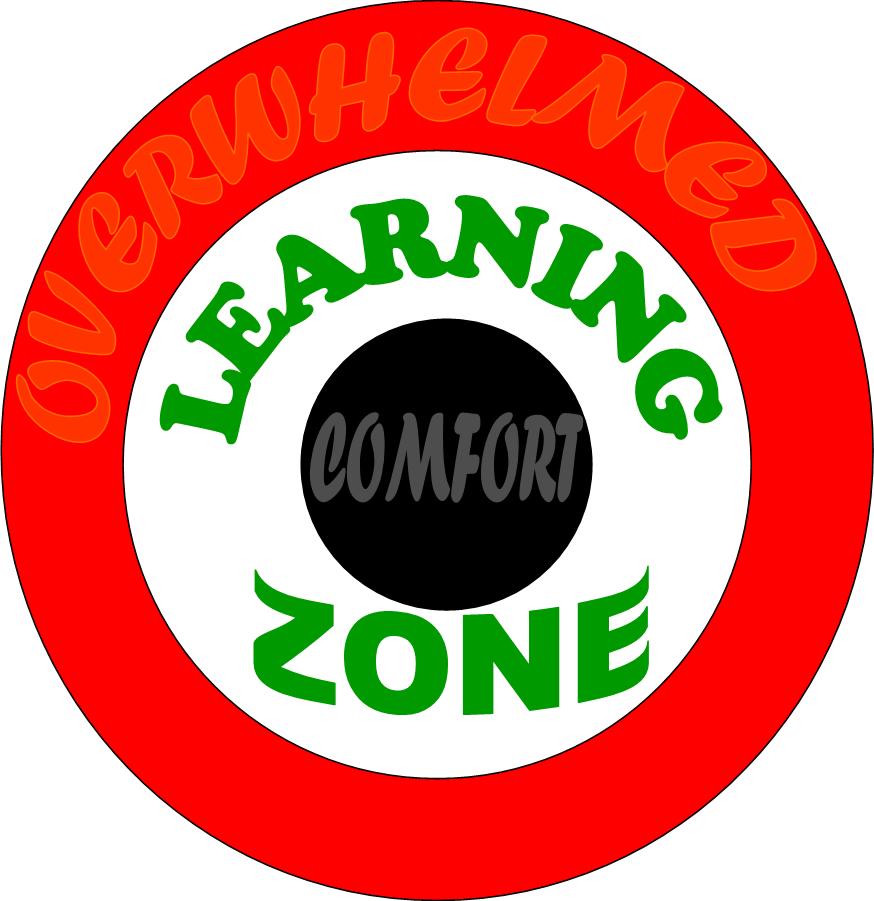

Years ago I started using a diagram with players and staff. A bullseye with three rings:

Years ago I started using a diagram with players and staff. A bullseye with three rings:

The innermost circle is the Comfort Zone—familiarity, safety, things you can already do. Surrounding it is the Learning Zone—growth, discomfort, curiosity. Beyond that sits the Overwhelmed Zone, where attention collapses and perception shuts down.

My goal has always been to keep people in the Learning Zone. That's where observation sharpens. That's where development accelerates. Push too hard, you overwhelm them. Don't push at all, nothing changes.

What took me decades to understand: the Learning Zone doesn't expand. It stays constant. What changes is you. As you grow, your Comfort Zone expands inward. The Overwhelmed Zone narrows outward. What once felt terrifying becomes manageable. What seemed impossible becomes familiar.

If I could animate that model, I'd keep the green ring static while the black center slowly expands and the red outer ring contracts.

Growth isn't escaping discomfort. It's integrating it.

This same principle applies to crisis management. Your ability to see through chaos depends on how well you've trained your perception. Panic belongs to the overwhelmed zone. Calm observation lives in the learning zone. Mastery means you've expanded your comfort to include what once would have broken you.

Proportion and Distraction

During our Day 7 conversation, my mind drifted to humanoid robots. Not as distraction—as pattern recognition. The same problem appears everywhere. A robot's reasoning needs to scale to the humans it serves. Intelligence without proportion fails exactly like a staff meeting where the coach teaches three levels above comprehension.

A tall robot in a small room has the same problem an expert has speaking over novices' heads. Both fail to calibrate awareness to environment.

Thoreau's entire life was an experiment in calibration. He reduced the inputs of his world so he could perceive it more fully. Fewer possessions. Fewer distractions. Fewer false obligations. He wanted to match his consciousness to the scale of the natural world. Walden was an operating system optimized for attention.

What I've learned from him—and from my own failures—is that observation is an act of proportion. To see clearly is to see at the right scale.

The lilies taught me temporal patience: the world moves slower than I do. The staff meeting taught me cognitive patience: not everyone's perception unfolds at the same speed. The spider plants taught me developmental patience: growth happens when there's room to expand.

Each lesson is a variation on the same theme. Attention without proportion becomes blindness.

The Frustration of Seeing Differently

I've spent years being the one who sees connections others miss. It's easy to interpret that difference as superiority or alienation. But Thoreau reminds me the goal isn't to see more than others—it's to see more truly, and then teach others how to see in turn.

The work of the teacher, the coach, the architect of performance is to widen the world of attention without breaking it.

In practice, this means learning to live in the Learning Zone yourself. To stay there longer each time, even as comfort expands and overwhelm narrows. Observation sharpens with endurance. Seeing clearly isn't a gift. It's a muscle.

I used to think my role as a coach was to supply knowledge. Now I think it's to cultivate perception. Knowledge can be transferred. Perception must be trained.

Every system I've built—from Midcourt to The Performance Architect to the Temple School Notebook—is ultimately an attempt to systematize perception. To make observation teachable, scalable, repeatable.

The irony is that the very thing Alcott couldn't scale—dialogue—is what we're trying to scale now with AI. The challenge remains the same: how to preserve human nuance at human scale.

The Real Advance

The humanoid robots I imagined earlier might help with that one day. They'd need to be designed not just with intelligence, but with proportion—the ability to modulate reasoning to fit the emotional and cognitive scale of the humans they serve.

The real advance won't be speed or processing power. It'll be empathy coded as calibration.

And perhaps that's the heart of all this. Whether we're talking about Thoreau's pond, a tennis lesson, or an artificial mind, the problem of perception is the same: How do we align intelligence with the world's rhythm? How do we learn to see not more, but better?

The answer, I think, lies in what Thoreau called "the infinite expectation of the dawn." It's the willingness to stay awake, to keep observing even when nothing seems to happen. It's the discipline of watching a daylily long enough to understand that movement is everywhere, even when unseen.

The Lesson in the Wait

I never did catch one of those lilies opening.

But maybe that's the point.

The lesson wasn't to witness the bloom—it was to learn how to wait for it. To live at the pace of its unfolding. To understand that transformation happens whether I'm watching or not. The discipline isn't controlling the process. It's training my attention to recognize it when it arrives.

That same patience applies everywhere. To players on court. To staff in meetings. To spider plants on a windowsill. To the slow work of building systems that might finally solve what Alcott saw but couldn't scale.

Thoreau spent years at Walden training his eye to see the pond—not once, but continuously. Different light. Different seasons. Different moods. The pond didn't change. His capacity to perceive it did.

That's what the discipline of observation offers. Not mastery over what you see, but readiness for what it reveals. Not control of transformation, but recognition of its constant presence.

The world has always been moving. The question is whether we've trained ourselves to notice.

I'm sixty-three now. I've spent more time observing than I care to count. Courts, classrooms, systems, people. The discipline gets no easier. But I understand it better. Seeing clearly isn't about gathering more information. It's about being present to what's already there. Thoreau called it living deliberately.

The lilies kept blooming while I looked away. The players kept developing even when I wasn't watching. The world continued transforming without my constant supervision.

My job was never to catch every moment. It was to build my capacity to recognize them when they mattered most.

That's the discipline of seeing. And it's the work of a lifetime.

Never Miss a Moment

Join the mailing list to ensure you stay up to date on all things real.

I hate SPAM too. I'll never sell your information.