Part III: Debrief

Feb 03, 2026

Turning Data Into Understanding

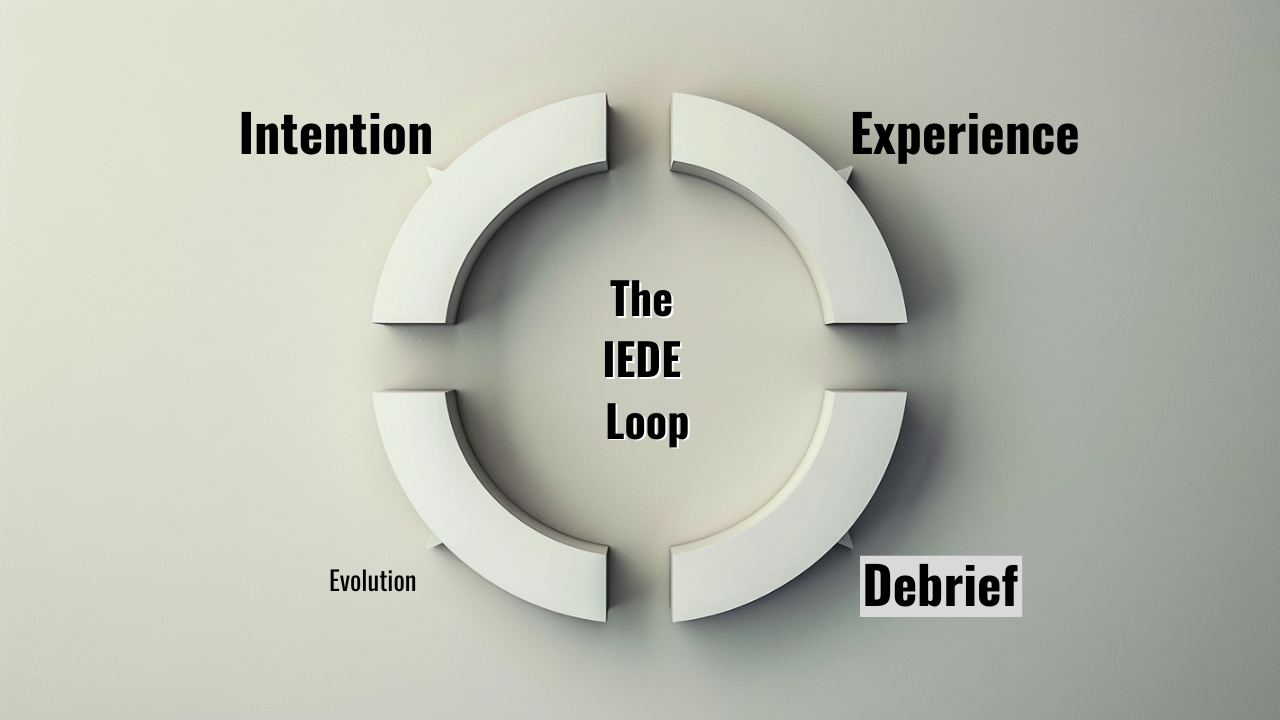

The third phase of the IEDE loop is where raw experience becomes usable knowledge. This is where the data collected under pressure gets examined, organized, and translated into insight. This is where the player stops feeling what happened and starts understanding what happened.

Debrief is not about judging performance. It is about extracting meaning.

Most post-competition conversations fail at this phase. A parent asks how it went. The player who lost says terrible. The player who won says great. A coach asks what happened. The player says I don't know, I just played well today or I couldn't get it together. These are not debriefs. These are emotional reactions to outcomes. Win or lose, the experience happened, but the learning stays buried.

Real debrief requires structure. It requires discipline. It requires the player to move from feeling to thinking without losing the accuracy of what they noticed during the experience. That movement is harder than it sounds. Memory distorts quickly. Emotion colors observation. Narrative rushes in to replace data. Without a clear process, the debrief becomes storytelling instead of analysis.

This essay examines Debrief, the phase where experience becomes education.

Why Debrief Cannot Happen During Experience

Debrief must wait until the experience ends. This is not arbitrary. It is structural. During competition, the player's job is to notice and attempt to regulate. During debrief, the player's job is to organize what they noticed and extract patterns. These are different cognitive tasks. They cannot happen simultaneously.

The player who tries to debrief during competition stops competing. Their attention splits. Part of their mind is trying to perform. Part of their mind is trying to analyze. Neither task gets full resources. Performance degrades. Observation becomes incomplete. The player ends up with neither clean data nor clean execution.

This is why coaching during competition disrupts both experience and debrief. When a coach offers analysis between games or at changeovers, they are asking the player to switch cognitive modes in the middle of data collection. The player must process the coach's interpretation while simultaneously generating their own observations. The two streams interfere. The experience becomes contaminated. The debrief happens prematurely with incomplete information.

The separation between experience and debrief is not a nicety. It is a requirement. Experience generates data. Debrief processes data. Mixing them produces neither.

The Window of Accuracy

The debrief must happen soon after the experience ends, but not immediately. There is a window. Too soon and the player is still flooded with emotion. Too late and memory has already begun reconstructing.

The ideal window is between ten minutes and two hours after competition ends. Early enough that sensory memory is still vivid. Late enough that the nervous system has begun to regulate. Inside that window, the player can access what they noticed without the distortion that comes from emotional flooding or narrative distance.

Outside that window, accuracy degrades. The player who waits until the next day to debrief is no longer working with data. They are working with a story their mind has already constructed about what happened. That story will contain truth, but it will also contain interpretation, justification, and emotion. The raw observations are gone.

This is why most families miss the debrief window entirely. They leave the tournament. They drive home. They eat dinner. They move on. By the time anyone thinks to discuss the match, the experience has already been processed into narrative. The player knows how they feel about what happened. They no longer have clean access to what actually happened.

The debrief window closes whether you use it or not. The choice is whether to extract insight while it is still available or let the experience dissolve into impression.

When Waiting Is Necessary

For most matches, debrief within the standard window is both possible and preferable. Win or lose, the player can access what they noticed while memory is fresh. The emotional intensity of a typical tournament match, even a tough loss, subsides enough within an hour to permit examination.

But at the highest levels, after outcomes that carry exceptional weight, the standard window can be inaccessible. A player who just lost a Grand Slam semi-final in five sets may need days before they can examine the experience without emotional flooding. A player who just won their first major title may be too overwhelmed with relief to debrief effectively within hours. In these rare cases, waiting is not avoidance. It is recognition that some experiences require time before they can be processed.

This creates the problem already described. Memory reconstructs. The player who waits a week is working with narrative, not observation. This is where immersive replay becomes essential. An environment that can recreate the match experience with enough fidelity, not just video but spatial presence, temporal pacing, physiological cueing, can reactivate sensory memory even after days or weeks have passed. The player re-experiences rather than remembers. The debrief can proceed with accuracy even though time has intervened.

This is not the same as watching film. Film review is external observation. Immersive replay is internal reactivation. The player is placed back into the conditions that produced the data. Their nervous system responds. The observations that were buried under emotional flooding become accessible again.

Immersive replay also permits physiological monitoring that competitive rules prohibit. During sanctioned competition, no wearables, no biometric sensors, no real-time measurement of the nervous system's response to pressure. The player can only access what they consciously notice. But during replay in a controlled environment, the full physiological signature becomes visible. Heart rate variability. Respiration patterns. Muscle tension. Galvanic skin response. The debrief is no longer limited to what the player remembered noticing. It can examine what the body actually did, including the signals that occurred below conscious awareness. This extends observation beyond subjective memory into objective measurement.

Founders' Room debrief at approximately one hour after competition is the ideal for any significant match. Win or loss. The emotional flood has subsided enough to permit examination. The sensory memory remains vivid. The physiological monitoring can capture what the player could not access during competition. This is the optimal condition for extracting insight. A player who just executed their patterns perfectly under pressure benefits from understanding exactly what their nervous system did when everything worked. That data is just as valuable as understanding what happened when everything broke.

But tournament logistics often prevent it. When the next match is in ninety minutes, there is no time for immersive debrief. When multiple matches occur in a single day, the window closes before it can be used. In these cases, verbal debrief within the standard ten-minute to two-hour window becomes the accessible method. Not optimal, but functional. The player and coach can still reconstruct observations and connect them to intention before memory distorts.

When neither option is available, when emotional intensity is too high or logistics too compressed, the debrief must wait. This is where immersive replay extends what would otherwise be lost. Days or even weeks later, the player can re-enter the experience with enough fidelity to reactivate sensory memory and complete the debrief that circumstances prevented.

The hierarchy is clear. Founders' Room at one hour is best. Verbal debrief within two hours is good. Immersive replay when necessary preserves what would otherwise become narrative. The principle remains constant. Fresh sensory access drives accuracy. The method adapts to preserve that access when circumstances limit it.

What Debrief Is Not

Before describing what debrief does, it is useful to name what it does not do. Most conversations labeled as debrief are actually something else.

Debrief is not reassurance. It is not telling the player they did their best or that the result does not matter. Those statements may be true. They may be kind. But they are not debrief. They are emotional management. Emotional management has a place, but it is not the same work as extracting learning.

Debrief is not celebration. After a win, it is not congratulating the player and moving on. Celebration feels appropriate. The player worked hard and succeeded. But celebration without examination leaves questions unanswered. Was this win the result of capability growing or competition weakening? Did the player's tolerance get tested or did pressure never arrive? Celebration alone teaches nothing about what actually happened.

Debrief is not tactical correction. It is not explaining what the player should have done differently or listing the technical errors that led to the loss. Tactical correction addresses execution problems. Debrief addresses awareness problems. The two are connected, but they are not the same conversation.

Debrief is not motivational speech. It is not pumping the player up for the next match or reminding them of their potential. Motivation might help the player feel better. It does not help the player understand what their nervous system revealed under pressure.

Debrief is not blame assignment. It is not identifying whose fault the loss was or explaining why the player was not prepared. Blame shuts down learning. It replaces observation with judgment. When blame enters the conversation, debrief ends.

Real debrief is something quieter and harder. It is the disciplined examination of what the player noticed during the experience. It is the process of organizing observations into patterns. It is the work of connecting those patterns back to the intention that was set before competition began. This work matters just as much after wins as after losses.

The Structure of Debrief

Useful debrief has three layers. Each layer serves a distinct function. Each layer depends on the one before it.

The first layer is recounting. The player describes what happened in sequence. Not what they felt. Not what the score was. What they noticed. This layer establishes the factual base. It separates observation from interpretation. It forces the player to access sensory memory rather than emotional memory.

The questions at this layer are simple. What did you notice about your breathing in the first set? When did your tempo start to change? What happened to your decision making after you lost serve? What happened to your decision making when you were ahead? Where did you feel tension first? When did tension release? The player is not explaining why things happened. They are naming what happened.

This layer is harder than it appears. Most players jump immediately to interpretation. After a loss, they say I was nervous instead of my breath was shallow. They say my opponent was playing too well instead of I started rushing my decisions after the third game. After a win, they say I was confident instead of my tempo stayed consistent. They say my opponent made mistakes instead of I maintained aggressive spacing throughout. Recounting requires the player to stay at the level of sensation and behavior regardless of outcome. That precision is what makes the next layer possible.

The second layer is integration. The player examines whether the experience matched their intention. This is where the pre-competition purpose becomes the lens for analysis. If the player intended to test their ability to stay aggressive under pressure, the question becomes did you? And if not, when did it shift? This layer connects observation to developmental purpose.

The questions at this layer are relational. You said you were testing your ability to reset quickly after errors. What did you learn? Did your resilience improve from the last event? Did you notice the moment your tolerance threshold got crossed? How deep did you fall when it happened? Or did the pressure never reach your threshold? If not, what does that tell you about whether this level of competition is still testing you? The player is no longer simply describing. They are measuring their current capabilities against their own baseline.

This layer is where growth becomes visible. Not growth as outcome. Growth as awareness. The player who can name the exact moment their behavior changed is more developed than the player who knows only that something went wrong. The player who can name that their threshold was never crossed is more developed than the player who only knows they won easily. The player who can describe how quickly they recovered after going down a break is more developed than the player who only knows they came back to win. Integration is the layer where precision reveals development regardless of outcome.

The third layer is reorganization. The player decides what changes based on what they learned. This is not tactical adjustment. This is model adjustment. The player is updating their internal understanding of how they respond under pressure. They are revising their beliefs about their own capabilities. They are identifying what needs attention before the next experience.

The questions at this layer are forward looking. What do you understand now that you did not understand before? What pattern showed up that you need to watch for next time? What capability needs development? What belief about yourself turned out to be inaccurate? The player is not fixing the past. They are recalibrating for the future.

These three layers build on each other. Without recounting, integration has no foundation. Without integration, reorganization has no target. The structure prevents the debrief from collapsing into reaction or advice. It keeps the conversation grounded in what the player actually experienced.

The Role of Questions

Debrief is not a lecture. It is a guided examination. The coach or parent facilitates. The player does the thinking. The quality of the debrief depends entirely on the quality of the questions asked.

Good questions are open and specific. They invite observation without suggesting answers. What did you notice about your breathing? is a good question. Your breathing was terrible, wasn't it? is not a question at all. It is a judgment disguised as inquiry.

Good questions direct attention without controlling perception. When did your tempo change? directs the player to examine tempo. It does not tell them what they should have noticed or what it means. The player must access their own memory and describe what they observed. That effort is where learning happens.

Good questions also sequence correctly. You cannot ask about integration before the player has recounted what happened. You cannot ask about reorganization before the player has measured against intention. The layers must build in order. Skipping steps produces shallow insight.

The coach or parent who asks good questions does not need to provide answers. The player's own observations, examined with care, generate the insight. The role of the facilitator is not to be smart. The role is to keep the player in contact with their own experience long enough for patterns to emerge.

This is harder than it sounds. Most adults cannot resist the urge to teach during debrief. They hear the player describe a problem and immediately offer solutions. They hear the player express frustration and rush to provide comfort. Both impulses derail the process. The player stops thinking and starts receiving. The debrief becomes instruction instead of examination.

The discipline required of the facilitator is to ask the next question and wait. Wait while the player searches memory. Wait while the player organizes thought. Wait while the player finds language for something they felt but did not yet understand. That waiting is the space where learning occurs.

Why Most Debriefs Fail

Most debriefs fail because they start with judgment. The first question is did you win or did you lose? If the answer is lose, the conversation shifts immediately to what went wrong. If the answer is win, the conversation ends with congratulations. Either way, the player's attention never reaches the data. After a loss, attention moves to blame and justification. After a win, attention stops at satisfaction. The data collected during experience disappears under the weight of outcome evaluation.

Judgment-based debrief teaches the player that competition is about verdict, not revelation. Losses mean failure and must be explained away. Wins mean success and need no examination. This prevents the player from seeing competition as research. Over time, this produces two problems. After losses, the player becomes risk-averse. They stop testing themselves. They play not to lose. After wins, the player develops false confidence. They believe they understand what worked when they only know the outcome. Neither pattern produces learning.

Debriefs also fail when they skip the recounting layer and jump straight to conclusions. After a loss, the player says I played badly and the coach says here's what you need to fix. After a win, the player says everything clicked and the coach says keep doing that. No examination of what the player actually noticed. No connection to intention. No measurement of mental toughness components. Just reaction imposed from outside. The player may adjust behavior, but they do not improve awareness. They become dependent on external diagnosis instead of building internal perception.

The third common failure is narrative hijacking. The player begins describing what happened and someone interrupts with an interpretation. After a loss: I know exactly what happened, you started doubting yourself. After a win: I know exactly what happened, you believed in yourself today. These narratives may contain truth. But they replace the player's observation with someone else's story. The player learns to accept external interpretation rather than trust their own perception.

All three failures produce the same result. The player accumulates experience without developing understanding. They compete more and learn less. They remain dependent on coaches and parents to tell them what happened and what it means. Agency never develops. The debrief becomes another form of instruction instead of a tool for self-awareness.

The Difference Between Self-Directed and Facilitated Debrief

Early in development, debrief must be facilitated. The player does not yet have the structure or discipline to examine their own experience without guidance. A coach or parent asks the questions that keep the player at the right level of observation. Over time, the player internalizes the structure. They begin asking themselves the questions. The debrief becomes self-directed.

Self-directed debrief is the goal. It is the marker that the player has moved from dependent learning to autonomous learning. The player who can sit down after a match and walk themselves through the three layers without external prompting has developed a permanent learning tool. That tool works in every domain. It transfers beyond tennis. It becomes part of how they process any high-pressure experience.

The transition from facilitated to self-directed debrief takes years. It requires hundreds of repetitions. But once the player internalizes the structure, they no longer need someone else to extract meaning from their experience. They carry the loop inside themselves. That self-sufficiency is more valuable than any technical skill they will ever develop.

This is the part of development most systems never build. They teach technique. They develop fitness. They train tactics. But they never teach the player how to examine their own experience. The player stays dependent on external feedback. When coaching ends, development ends. The player never learned how to learn.

Self-directed debrief solves this problem. It turns the player into their own coach. Not in the sense of correcting technique, but in the sense of extracting insight from experience. That capacity is what allows development to continue long after formal training stops.

Connecting Debrief to Intention

The debrief is incomplete if it does not return to the intention set before competition. The player said they were testing something. The debrief must examine whether they tested it. This connection is what keeps the loop closed.

If the player intended to test their ability to maintain aggression under pressure, the debrief asks did you? The answer is not yes or no. The answer is a description. Yes, in the first set. No, after I got broken in the second. I felt my decision making shift from proactive to reactive around the fourth game. Or: Yes, throughout the match. My opponent never created enough pressure to force me defensive. That tells me I need stronger competition to actually test this. Both descriptions are data. Both get carried forward.

If the player intended to measure their resilience, the debrief asks how quickly did you recover after disruption? Again, the answer is a description. I recovered between games after the first disruption. I did not recover before the end of the set after the second disruption. Or: I was never disrupted enough to need recovery. The match stayed within my control throughout. That comparison reveals whether resilience improved, stayed flat, degraded, or was never tested. All of those are valuable measurements for the player's developmental record.

Without the connection back to intention, the debrief drifts. It becomes a general discussion about the match. Those discussions can be useful, but they are not systematic. They do not build a cumulative record of growth. They do not track whether the player is developing the components they said they wanted to develop.

The intention-debrief connection is what makes the loop a system instead of a series of isolated events. Each cycle builds on the previous one. The player is not starting over every tournament. They are continuing a long-term developmental project. That continuity is what allows real growth to accumulate.

What Wins Reveal

Wins need debrief just as much as losses. This is counterintuitive. A player wins and the natural response is to move on. The result speaks for itself. But wins reveal different information than losses, and that information is equally important for development.

A comfortable win reveals whether the player's current level of competition is still sufficient to test their capabilities. If a player intended to test their tolerance threshold and won easily without ever feeling pressured, the debrief shows that threshold was never approached. That is valuable data. It means the next test requires stronger opposition or different conditions.

A close win reveals which mental toughness components held under pressure. If a player went down a break, recovered, and won, the debrief examines the recovery. How quickly did resilience activate? How far did fortitude drop before resilience engaged? What changed in their awareness or behavior during the recovery? These patterns are only visible when the player wins under stress, not when they lose under stress.

A win after adjusting strategy reveals whether adaptability is developing. The player started with one approach, recognized it was not working, adjusted, and succeeded. The debrief asks what they noticed that triggered the adjustment. How quickly did they recognize the need to change? What internal process allowed them to shift approach mid-match? This awareness of their own adaptive process is what makes future adaptation faster and more reliable.

Wins also reveal false confidence. A player might win and believe they have solved something when the truth is their opponent never tested them. The debrief after a win prevents this. It asks whether the conditions of the match were sufficient to validate what the player believes they learned. If not, the apparent lesson becomes suspect. The player learns to distinguish between validated capability and untested assumption.

The pattern is consistent. Losses reveal where capabilities broke. Wins reveal whether capabilities were tested. Both are necessary for a complete picture. Both require the same disciplined examination. Both feed the same developmental record. The player who only debriefs losses only has half the data. The player who debriefs both builds a complete map.

When Debrief Reveals Calibration Problems

Sometimes the debrief reveals that the intention was poorly calibrated. The player set an intention to test something, but the experience showed they were not ready to test it yet. Or the experience revealed a different problem than the one they expected. This is not failure. This is discovery.

Calibration problems are valuable information. They show where the player's self-awareness is still forming. They reveal gaps between what the player believes about themselves and what is actually true. Those gaps are where the most important learning happens.

A player who intended to test their ability to execute patterns under pressure might discover through debrief that their tolerance threshold is lower than they thought. They did not get far enough into pressure to test pattern execution because they crossed their tolerance threshold earlier than expected. That discovery changes what needs attention. The next intention must address tolerance first.

This is why debrief cannot be skipped. It is the feedback mechanism that adjusts the entire loop. It tells the player whether their intention was accurate, whether their observation during experience was clean, and whether their understanding of their own development is current. Without debrief, the player keeps setting intentions that miss the real work. With debrief, the intentions become progressively more accurate.

Debrief as Preparation for Evolution

The final function of debrief is to prepare the ground for evolution. Evolution is the fourth phase of the loop. It is where the insight extracted during debrief gets integrated into the player's behavior, beliefs, and baseline capabilities. But evolution cannot happen without debrief. Evolution requires organized understanding, not raw experience.

Debrief is the bridge between what happened and what changes. It takes the fragmented observations collected during experience and organizes them into coherent patterns. Those patterns are what the player carries forward. Those patterns are what determine whether the experience makes them better, worse, or leaves them unchanged.

This is why debrief is not optional. It is not something you do when you have time or when the player feels like talking. It is the phase that determines whether experience becomes growth. Without it, the player accumulates stress without accumulating wisdom. They compete more and develop less. The loop breaks at the exact point where learning should occur.

The Long-Term Function of Debrief

Over years, debrief builds a record. Not a record of wins and losses. A record of patterns revealed under varying conditions. The player who goes through structured debrief after every significant competition develops a map of their own nervous system. They know their tolerance threshold. They know how far they fall when they cross it. They know how quickly they recover. They know whether difficulty makes them better or worse over time. They know which levels of competition test their capabilities and which levels leave them unchallenged.

That map is the most valuable asset an athlete can develop. It is more valuable than technique. It is more valuable than fitness. It is more valuable than ranking. The map allows the player to navigate pressure with accuracy instead of hope. They know what to watch for. They know when intervention is needed. They know what intervention actually works for them. They know when they need stronger opposition to continue developing.

This knowledge transfers. The player who understands their own pressure response in tennis will recognize the same patterns when they enter high-stakes situations in other domains. They will know when their tolerance is being tested. They will notice when their fortitude is slipping. They will recognize when they need to activate resilience. They will measure whether new experiences are making their baseline stronger or weaker.

This is how the Alcott Dilemma gets solved. The problem is not that individualized development cannot scale. The problem is that most development systems never teach the player how to continue developing themselves. Debrief is the tool that makes self-directed development possible. It is the mechanism that allows learning to transfer across contexts and persist across time.

The player who learns to debrief well learns to learn permanently. That capacity is what I have been trying to build for thirty five years. Debrief is where that capacity gets trained. Without this phase, everything else remains theoretical. With this phase, the loop closes and development becomes inevitable.

Never Miss a Moment

Join the mailing list to ensure you stay up to date on all things real.

I hate SPAM too. I'll never sell your information.