Running Public Tennis Centers: Lessons from the Trenches

Aug 31, 2025

This chapter contains a call-to-action for tennis parents to understand what it really takes to operate a public facility and how these lessons apply to choosing the right development environment for their kids.

Most tennis parents think running a tennis center is like running any other business—you set up shop, advertise your services, and watch the money roll in. They assume the biggest challenges are keeping the courts clean and finding decent instructors.

They couldn't be more wrong.

Running a public tennis center is one of the most brutal operations you can attempt in tennis. It's an "eat what you kill" business where there's no membership base writing monthly checks to cover your overhead. Every dollar has to be earned fresh each day, and if nobody shows up, the phone doesn't ring unless it's a wrong number.

I learned this the hard way when my partner Kim Kurth and I took over Samuell Grand Tennis Center in Dallas. What we inherited was a facility so broken down that some days literally nobody walked through the doors. The phone sat silent except for occasional misdials.

But to understand how we got there, I need to back up to 2007. I was living in Charlotte, NC, and facing a move to Dallas-Fort Worth. My daughters' stepfather was being relocated from Woodstock, GA to Plano, TX for his job with T-Mobile, and I refused to be the kind of father who settles for two weeks in summer and every other Christmas. Coming from smaller communities, I had no idea how massive DFW actually was. I needed someone to show me around the area, and not knowing how else to find a local guide, I did what any single guy would do—I went on Match.com.

That's how I met Kim Kurth. She was the Executive News Producer at the CBS owned-and-operated station in Dallas–Fort Worth. She had a journalism degree, twenty-plus years in broadcast, and a track record at CBS DFW growing the morning show's ratings. On air, she knew how to build an audience. After dating for a few months, we took a trip to Massachusetts so she could meet my family. We were having lunch in Gloucester with my sister and brother-in-law when Kim got the call that would change everything.

The station was laying people off—this was 2008, and the economic conditions were brutal across all industries. Because Kim was last in, she was first out. We looked at each other across that restaurant table in Massachusetts and made a decision that no longer made sense for me to wait to move. We went back to Charlotte, packed my belongings into the garage of the house I was renting, and drove to Frisco, Texas, where I took up residence in the guest room of her parents' house.

Neither of us knew it at the time, but that economic upheaval that cost Kim her television career would eventually lead us to the tennis center opportunity that wouldn't come until 2010.

I was operating my program out of rented courts at the University of Texas at Dallas (UTD), where Bryan Whitt was the head tennis coach. Bryan had been awarded the contract for Samuell Grand Tennis Center (host site for a 1965 Davis Cup tie) but quickly realized that turning around a failing public facility wasn't compatible with his role as head tennis coach at a major university. When he decided to give up the contract, he called to ask if I would be interested in assuming it.

The timing was devastating. Bryan called on the same day my mentor, Ernie Peterson—the 2003 US Olympic Committee Developmental Coach of the Year—passed away from a stroke. I was too distraught to take his call, so Kim answered and told him I couldn't talk. When I finally called Bryan back, Kim and I were driving from Frisco to College Park, Georgia, for Coach Peterson's memorial service.

Bryan explained that he was planning to turn the keys back to the City of Dallas on Monday, and if I wanted a chance to take over the facility, I needed to be there. I told him where we were and where we were going, explaining that I definitely would not be there, but asked him to call me the following week if the opportunity was still open.

Coach Peterson had been telling me for years that my time would come, that I would take what he'd started and go beyond it. As I said in a video blog I posted around that time, "I always thought I was ready. He told me I would be one day, and now it's time to step up. And I'm not so sure, but I'm going to do it anyways, because it's what you would have expected of me."

That phone call about Samuell Grand came at the exact moment when I was grappling with stepping into the role Coach Peterson had been helping prepare me for almost my entire career. Looking back now, I can see this wasn't coincidence—it was part of a string of divine interventions that had been orchestrating my path for years.

Think about the precision of the timing: Kim losing her television career in 2008 during the economic downturn, making her available for a partnership neither of us could have planned. Me refusing to be an every-other-Christmas father, forcing the move to Dallas. Coach Peterson's passing on the exact same day the Samuell Grand opportunity presented itself. Bryan Whitt realizing he couldn't handle both his university coaching position and the tennis center turnaround, choosing to call me specifically.

Any one of those elements happening differently would have changed everything. But together, they created the perfect conditions for what was about to unfold.

Kim, with her journalism degree and 25 years of television production experience, looked around at what we'd eventually get ourselves into and said what any rational person would say: "We're either crazy or this is an amazing opportunity."

She was right on both counts. But what neither of us understood yet was that we weren't just taking on a business opportunity. We were stepping into roles that had been prepared for us through a series of seemingly unrelated events that only made sense when viewed through the rearview mirror and as part of a larger design.

The Reality Check Nobody Talks About

Here's what the tennis industry won't tell you about public facilities: they're supposed to fail. The business model is designed to barely break even, assuming you can keep your head above water at all. Unlike private clubs where members pay dues whether they use the courts or not, public centers live or die based on daily activity. No membership cushion. No guaranteed revenue stream. No wealthy board members to bail you out when things get tight.

Kim understood this challenge better than most. As a former Executive Producer at CBS DFW, where she'd successfully increased morning show ratings by 3 points, she knew how to build audiences and create compelling content. But television has advertisers and network support. Tennis centers have court fees and lesson payments from people who can easily decide to play somewhere else.

"Running a public tennis facility," I told people back then, "is one of the most challenging operations you can do in tennis." What I didn't mention was how addictive it becomes once you figure out the formula.

The Transformation That Nobody Expected

When we took over Samuell Grand, it was the worst-performing facility in the Dallas public tennis system. Twenty courts of wasted potential sitting on historic ground where Arthur Ashe had played Davis Cup in 1965. The facility that should have been the crown jewel of public tennis had become a place parents actively avoided, going so far as to making sure their children used the bathroom before leaving home.

But here's the thing about being at the bottom—you have nowhere to go but up, and every small improvement feels like a massive victory.

Kim became our Chief Operating Officer, bringing systems thinking from her television background. While I focused on tennis programming and player development, she tackled the operational challenges that most tennis professionals ignore until they destroy the business. Revenue tracking. Customer communication. Community building. Marketing that actually worked.

Television production taught her something crucial: content quality means nothing if nobody knows about it or shows up to consume it. The best tennis instruction in the world is worthless if parents don't understand its value or can't find convenient ways to access it.

The Systems That Changed Everything

Most tennis facilities operate on hope and good intentions. Hope that players will keep coming. Hope that weather won't cancel too many programs. Good intentions about providing quality instruction. Hope and good intentions don't pay rent or salaries.

Kim introduced systematic approaches to problems that most tennis centers handle through crisis management. Instead of scrambling when rain threatened to cancel programs, we developed automated communication systems to notify families immediately. Instead of hoping people would remember to sign up for camps, we created digital newsletters with clear calls to action and deadline reminders.

Our rain plan fit in one text:

Rain Plan (sample text)

"Session moved indoors to Recreation Center Gym 5–6p; makeup Sat 10a; confirm Y/N."

Why it works: clarity, options, timestamped

The RainOut management system Kim implemented in 2011 seems obvious now, but it was revolutionary then. Parents could get real-time updates, connect with other families, and see constant evidence that their kids were part of something bigger than just weekly lessons. Community building became revenue building because engaged families become loyal customers.

Her television background showed up in unexpected ways. She understood that perception often matters more than reality in the short term, but reality always wins in the long term. So we focused on making sure every family interaction exceeded expectations while systematically improving the actual quality of everything we offered.

The Numbers That Tell the Real Story

After about a year of systematic improvements, Kim suggested we sit down and grade everything we'd tried on a 0-3 scale. Programs rated 3 got doubled down on. Programs rated 0 got eliminated completely. Everything else got modified or replaced.

We graded every program. No sacred cows:

The 0–3 Program Grading System

0 = eliminate, 1–2 = modify/replace, 3 = double-down

Reviewed quarterly; cut 0s within 30 days

This evaluation process became the foundation for 56 of 57 consecutive months of year-over-year revenue growth. Not growth compared to some arbitrary projection, but actual growth compared to the same months in previous years. Month after month, for nearly five years straight. That streak meant payroll predictability and reinvestment—not luck.

By July 2015, we were generating tens of thousands of dollars in total monthly revenue across all streams. Tennis lessons accounted for 80.2% of the business. Court rentals brought in 9.1%. Merchandise sales reached over $2,000/month. Food and beverage added almost another $1,000. But the most important number was attendance: 2,560 people came through our doors that month compared to 1,734 the year before—a 47.6% increase. In retail terms, that's nearly a 50% jump in families choosing us. Real proof that systems beat weather and wishful thinking.

These weren't just numbers on a spreadsheet. They represented families choosing to invest their time and money in what we'd built together. They represented kids developing life skills along with tennis skills. They represented a community gathering place that people actually wanted to be part of.

The Recognition Nobody Saw Coming

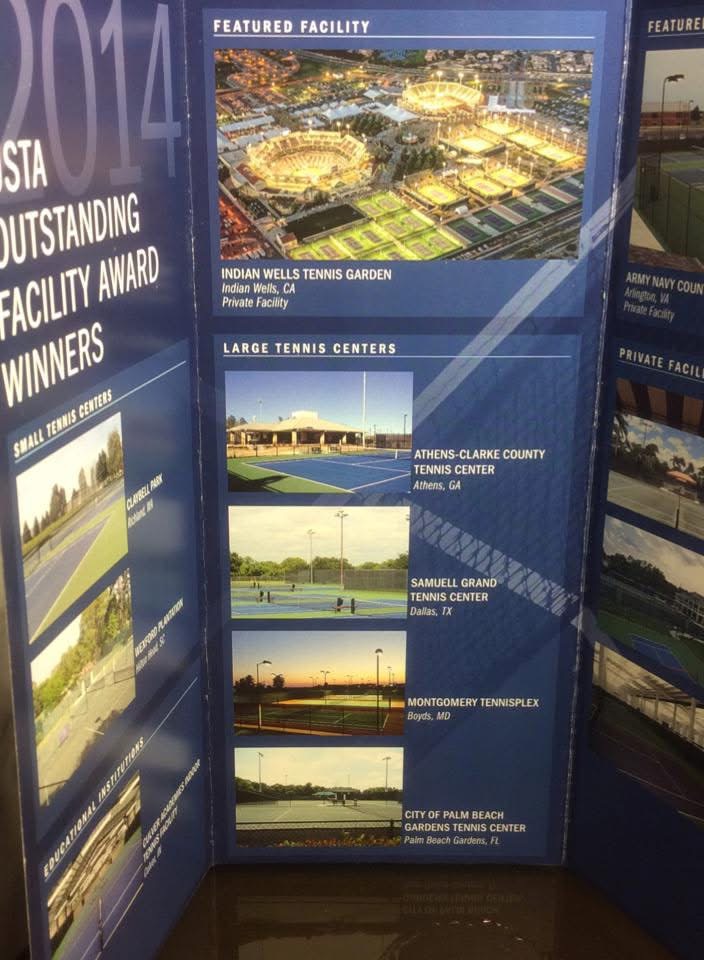

In 2014, something happened that shocked everyone, including us. The USTA selected Samuell Grand Tennis Center as the National Facility of the Year for Large Public Tennis Centers.

Let that sink in. A facility that had been "the worst of the worst" just four years earlier was now considered the best public tennis facility in the entire country. Not the best in Texas or the best in the Southwest. The best in America.

Kim's reaction was typical of her approach to everything: "Now we have to figure out how to deserve this award every single day going forward." No resting on accomplishments. No victory lap. Just the recognition that excellence is a daily commitment, not a one-time achievement.

The award validated our systematic approach, but it also highlighted something most people never consider: the gap between potential and performance at most tennis facilities is enormous. We hadn't created some revolutionary new approach to tennis. We'd simply done the basic work of running a professional operation while most of our competitors were winging it.

The Challenge That Changes You

Running a public tennis center forces you to become a different kind of tennis professional. You can't rely on captive audiences or inherited advantages. Every family who walks through the door is making an active choice to be there, and they can make a different choice next week if you don't earn their continued investment.

This was a complete shift from the elite individual coaching I'd been doing in Charlotte. There, I'd worked with players like Thai Kwiatkowski and ReeRee Li who were destined for the highest levels of competition. Thai would go on to win the NCAA championships (three times team Champion at University of Virginia and Men's Singles Champion his Senior Year), ReeRee would captain her team at Yale—these were players whose paths were already pointing toward major achievements. At Samuell Grand, we were starting from scratch with families who were just discovering tennis, trying to create a community where people wanted to spend their time.

The reality changed how I thought about player development completely. It wasn't enough to have good intentions about helping kids improve. We had to create visible, measurable progress that parents could understand and players could feel proud of. We had to build community connections that made families want to stay involved even when their kids hit rough patches or temporary plateaus.

For tennis parents evaluating programs: Look for facilities that can show you systematic progress tracking, not just subjective assessments. Ask how they measure development and whether other families have followed coaches from facility to facility—that's the ultimate vote of confidence.

The Power Bands achievement system we developed came directly from this pressure. We needed a way for players to see their progress, parents to understand their investment, and coaches to track development systematically. The result was 158 players across three skill levels with an 84.8% engagement rate—numbers that would make most youth programs jealous.

But the real success wasn't in the numbers. It was in the text message I got from a young man who started in middle school telling me he'd been accepted to a high-level college. It was watching elementary school kids grow into high school students who still called the tennis center home. It was families following us from Samuell Grand to Fretz Tennis Center because they'd become part of something they didn't want to leave.

The Business Model That Actually Works

Here's what we figured out that most tennis centers miss: public facilities succeed by becoming community gathering places that happen to focus on tennis, not tennis facilities that happen to serve the community.

Nobody goes to a country club to learn tennis. They go to country clubs after they've learned tennis and want additional amenities like advanced booking, restaurants, and better locker rooms. Public facilities are where people come to try the game, develop foundational skills, and figure out if tennis fits into their family life.

This distinction changes everything about how you operate. Instead of trying to compete with private clubs on amenities, you compete on accessibility, community, and genuine care for player development. Instead of assuming families understand tennis culture, you educate them about what quality instruction looks like and why certain approaches work better than others.

Kim's communication background proved invaluable here. She understood that most families don't speak "tennis professional" and most tennis professionals don't speak "concerned parent." Building bridges between these communication styles became a core competency that separated us from facilities that assumed good tennis instruction would sell itself.

The Lessons That Transfer Everywhere

For tennis parents evaluating programs: The systematic approaches we developed at public tennis centers apply to any tennis development environment. Whether you're looking at private academies, country club programs, or recreational facilities, the principles Kim and I learned can help you identify quality operations from marketing-heavy mediocrity.

What smart tennis parents should look for:

Questions Smart Tennis Parents Should Ask Any Program

• How do you measure player progress monthly and yearly? • Show me last season's weather-cancellation plan and communications • What percentage of families return each session? (And why do those who leave, leave?) • What's your community touchpoint (Facebook group, newsletter) and how often do you use it? • How are new coaches trained so quality stays consistent?

Red flags: "We don't really track that," "We text when we can," "It depends on the coach." If you hear any of those, smile, thank them, and keep walking.

Look for facilities that track measurable progress, not just subjective assessments. Ask about systematic communication with families, not just end-of-session evaluations. Observe whether the operation runs on professional systems or personal relationships that might not scale or survive staff changes.

Watch how facilities handle challenges like weather cancellations, scheduling conflicts, or player frustrations. Quality operations have systematic responses to predictable problems. Mediocre operations handle every challenge like it's the first time they've encountered it.

Pay attention to community building efforts. Facilities that create genuine connections between families produce better long-term outcomes than facilities that treat each player as an isolated transaction. Tennis is a lifelong sport, and players who develop within strong communities are more likely to stay involved through the inevitable ups and downs of competitive development.

If a director can't show you last month's retention rate or how they'll communicate the next rainout, you're buying hope, not a system.

The Partnership That Made It Possible

None of this would have been possible without Kim Kurth as Chief Operating Officer. Her television production background, communication expertise, and systematic thinking provided the operational foundation that allowed the tennis programming to flourish.

While I focused on player development and coaching systems, Kim handled the business operations that determine whether good intentions translate into sustainable results. Revenue tracking, community engagement, parent communication, marketing strategy, staff coordination, facility maintenance—the hundreds of details that separate successful operations from well-meaning failures.

Her ability to translate tennis concepts into parent-friendly language proved especially valuable. Tennis professionals often assume families understand the development process, the time commitments required, or the reasoning behind certain training approaches. Aided by not even knowing how to keep score until she met me, Kim built communication systems that kept families informed and engaged throughout their tennis journey.

As she described it, "Words comprise less than 10% of effective communication." The other 90% comes from consistency between what you say and what you do, systematic follow-through on commitments, and genuine care for the people you serve. These principles guided every operational decision we made.

The End That Became a Beginning

Despite our success—or perhaps because of it—we were eventually forced out of running the Dallas public tennis centers. Political decisions that prioritized relationships over performance meant that the facility we'd taken from worst to first would be managed by someone else.

The day I recorded a video about our transition, the raw emotions poured out. "We're going from a place where we had security to now we have none, and we've got to figure it out. It's scary, yet I'm also supremely confident we're going to be successful," I said to the camera. "Just because you're scared about something doesn't mean you're also not going to be confident that you're going to be able to do it, because Kim and I don't fail at anything."

That wasn't bravado talking—it was pattern recognition. "We took a tennis center that was on its last legs, and we brought it to where we won national award for being one of the very best in the country, and we did it in about four years from nothing. We're not going to fail at this."

Kim and I talked about it during those final days at Fretz. We realized our story wasn't unique. "I think our story is the story of America," I told her. "Mid-50s, transition forced on us, figuring it out anyway." And the more we talked, the more we realized we weren't alone.

Leaving Fretz hurt. It felt like being pushed out of a house we built by hand. But the work had already done its deeper work on us. Kim and I didn't just learn how to run a center; we learned how to stand inside uncertainty with a system, a partner, and a community that believed in the next chapter.

What sustained us through that transition was something I'd learned years earlier from Molly Barker, founder of Girls on the Run. She'd told me about a conversation during a run with one of her original participants, where the young girl said:

"I think God has ideas. He takes those ideas, places them inside of people and then sends them to earth. Sometimes the ideas are too big to fit inside of one person, so He breaks them up into pieces and places them into different people. Then he gets the people and His ideas together on earth."

The tennis center success hadn't been about our individual capabilities—it had been about our piece of something much larger. Kim brought television production systems, communication expertise, and operational thinking. I brought player development methods and community building experience. Together, we carried pieces of an idea bigger than either of us could have managed alone.

The forced departure from public tennis centers wasn't an ending—it was preparation for the next phase of carrying our pieces forward. The systems we'd developed, the relationships we'd built, and the lessons we'd learned about systematic excellence became the foundation for everything that followed.

Running public tennis centers taught us that excellence isn't about having the best equipment or the most prestigious location. Excellence comes from systematic commitment to doing the basics better than anyone expects, day after day, year after year. It comes from understanding that tennis development is really community development with racquets involved. It comes from recognizing that parents are partners in the process, not obstacles to overcome.

Most importantly, it comes from building systems that serve players and families rather than making players and families adapt to inadequate systems. The same pressure that forces public centers to be excellent is exactly what families should seek in any program: measured progress, reliable communication, and a community you can feel. You don't need the fanciest facility; you need one that earns your trust every month. Ask for the system. Watch the follow-through. Choose the place that treats tennis for what it is: community development—with racquets.

The tennis industry would be transformed if more facilities operated with the systematic excellence that public centers demand for survival. That transformation is still possible. The question is whether enough people are willing to do the work required to make it happen.

Never Miss a Moment

Join the mailing list to ensure you stay up to date on all things real.

I hate SPAM too. I'll never sell your information.