The Hit List

Jan 14, 2026

There is a moment after certain losses when something lodges in a young competitor that does not fade on its own. It is not insight, perspective, or maturity. It is unfinished business. Anyone who has spent enough time around competitive kids knows the look. The match is over, the handshake has happened, the coach has delivered the appropriate calm words, and yet something remains unresolved. The body knows it before the mind can explain it. The loss does not feel complete. It has not been metabolized.

Most development systems rush to erase that feeling. They deliver the approved language about process and perspective, always meaning well. But what they often do, unintentionally, is throw the snowball away before it has done its work.

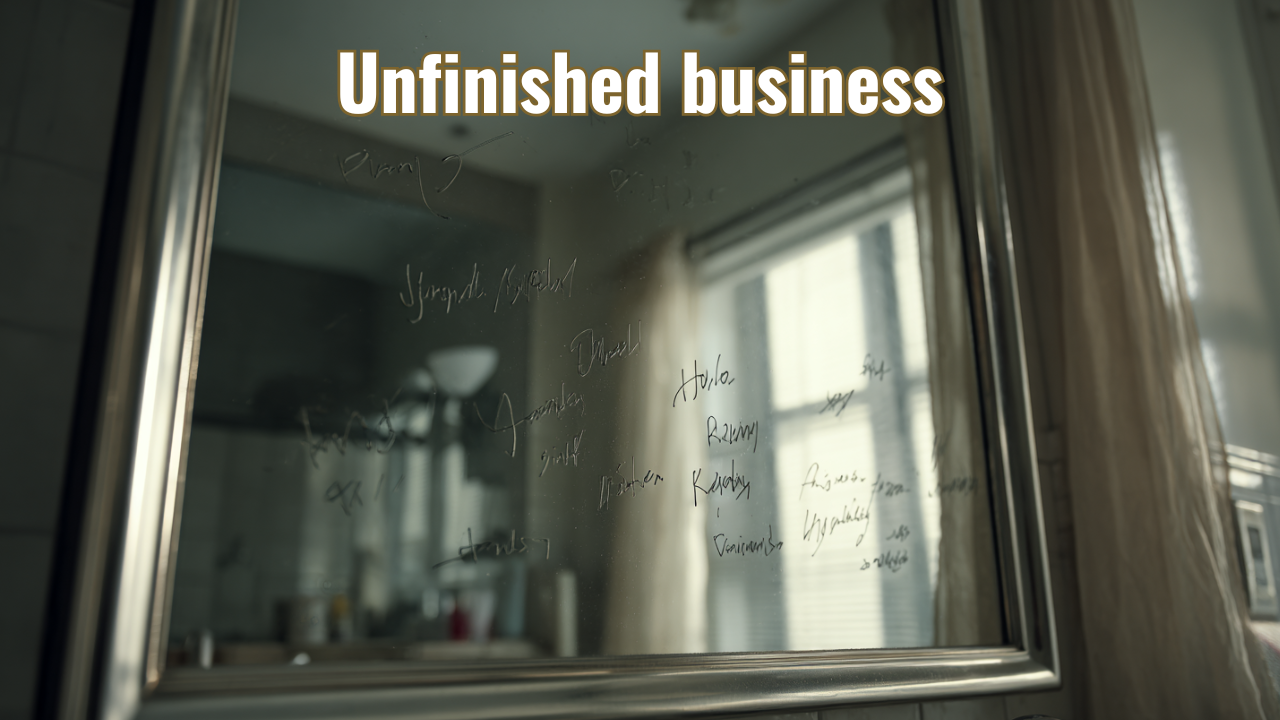

Years ago, I started doing something that made people uncomfortable. I asked junior players to keep a hit list. The term was not accidental. It was emotional on purpose. The list was simple: every time a player lost a match that mattered to them, the opponent's name went on the list. Sometimes I had them write those names on their bathroom mirror with a whiteboard marker. Morning and night, there it was. Not a motivational quote. A ledger.

This was not framed as calm reflection. It was framed exactly the way the kids felt it: You now owe that player a beat down. That phrasing mattered. It wasn't polite, but it was honest. It matched the internal narrative the child was already running, instead of asking them to replace it with adult-approved language they didn't yet believe.

The inspiration for this came, oddly enough, from a Bill Cosby routine about a kid named Junior Barnes. In the skit, the narrator gets humiliated by Junior Barnes in a snowball fight. Not a fair hit—a slush ball to the face, ice water down the clothes, public embarrassment. Worse, there is no justice afterward. No adult intervention. No resolution.

So the child does what children do when the world fails to balance the scales: he preserves the moment. He makes the perfect snowball, inscribes Junior Barnes' name on it, and puts it in the freezer. He waits across seasons. Winter passes, spring passes, July arrives. The grievance survives the weather. The humor lands when the mother throws the snowball away. The reckoning never comes. All that remains is a small, impotent act at the end. The audience laughs because they recognize the tragedy—the story never closed.

That skit captures something most development models miss: unfinished emotional narratives have persistence. If you resolve them too early, they don't disappear. They just go underground. If you ignore them, they repeat. If you contain them properly, they sharpen attention. The hit list was a way of containing them.

What the list did was not make kids invincible. That's important to say clearly. They did not beat every player they ever lost to. That was never the claim. What changed was the structure of their losses. Over a two-plus year stretch, six players in our program only lost once to someone they had previously beaten. They did lose matches. But they almost never lost twice to the same solved problem. And they beat numerous players later who had beaten them earlier. This was not dominance. It was non-recurrence. The system stopped looping.

Most junior players don't stall because they lack ability. They stall because the same losses keep reappearing under different circumstances. The opponent changes, the draw changes, but the explanation stays the same: "Just didn't play well." "Nerves." "Bad day." The hit list made repetition visible. Once a name was on the mirror, training changed. Not because the coach delivered better lectures, but because attention reorganized itself. Practices stopped being generic. Certain drills suddenly mattered more. Fitness stopped being abstract. Decision-making under pressure stopped being theoretical. The loss had a face.

This is where people get uncomfortable, because they want development to be clean and rational. They want learning to be analytical first, emotional later. But with young competitors, it often works the other way around. Emotion is the retention system. Before kids can convert losses into clean data, they need permission to remember them—not as trauma or shame, but as unresolved narrative. Something that still belongs to them.

The hit list wasn't about rage spiraling out of control. It was about aiming it. The emotion wasn't allowed to leak into sulking, excuses, or entitlement. It had one job: keep the problem alive until it was solved. That's a very different thing than telling a child to move on. Moving on is easy. Closing loops is hard.

One of the quiet failures of modern youth development is premature closure. Adults rush children through emotional discomfort because it makes the adults uneasy. The mirror didn't let the story dissolve. It didn't let the loss get sanitized into a lesson before it had reshaped behavior. It stayed there, unresolved, until the player either corrected the weakness or grew past the opponent. And when the loop closed, it stayed closed.

That's the key outcome—not revenge, not domination, but closure. Junior Barnes never gets hit in the skit. That's why it's funny and sad at the same time. The reckoning is denied. The ledger is erased by someone else. The child is left holding nothing. In this case, the reckoning happened on court, legally, and with the scoreline doing the talking. That difference matters.

Most systems act like the mother in the skit. They throw the snowball away too early. They remove the artifact before the child has used it. Then they wonder why the same losses keep happening, why confidence erodes, why effort stops converting into progress. The hit list wasn't polite. It wasn't therapeutic. It wasn't something you'd find in a coach education manual. It was effective. Because it respected how young competitors actually store meaning. It didn't ask them to be older than they were. It gave their emotion a structure instead of pretending it shouldn't exist.

Development doesn't require eliminating emotion. It requires designing containers for it. When you do that well, the results don't show up as bravado or trash talk. They show up statistically: fewer repeat losses, cleaner progression, less time wasted fighting the same ghost. The goal was never to raise kids who lived for payback. The goal was to raise kids who finished their stories. And in competitive sport, that turns out to be one of the most reliable forms of growth there is.

Never Miss a Moment

Join the mailing list to ensure you stay up to date on all things real.

I hate SPAM too. I'll never sell your information.