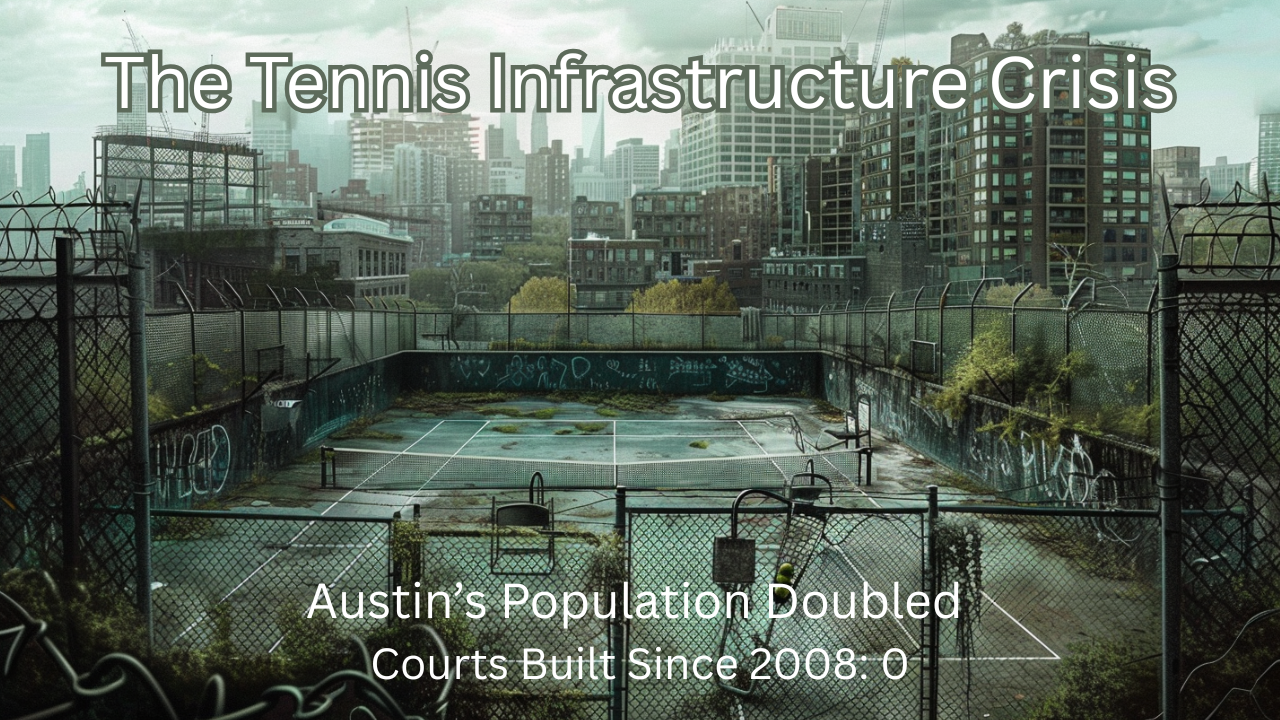

The Tennis Infrastructure Crisis No One Talks About

Sep 25, 2025

Austin's population doubled. Zero new tennis courts built since 2008.

That's not a typo. Austin Tennis Center opened sixteen years ago and remains the last public tennis facility built in a metro area that exploded from 650,000 to over 1.3 million residents. Meanwhile, existing courts crumble from lack of maintenance. School facilities stay locked post-COVID. Families scramble for playing time on a system that can't handle the demand.

Sound familiar? It should. Austin's crisis is happening everywhere. Minneapolis eliminated 39 of its 139 public tennis courts due to budget constraints. Los Angeles converts tennis courts to pickleball at Griffith-Riverside and Echo Park, sparking "Save Our Tennis Courts" campaigns. Denver closed pickleball courts at Congress Park and converted them back to tennis due to noise complaints - showing courts disappearing from both sides—tennis to pickleball in some cities, and pickleball curtailed elsewhere.

This creates a hidden bottleneck that's choking junior tennis development before it can begin.

The Math Doesn't Work

Dallas shows the same pattern with bigger numbers. The city maintains 280+ tennis courts across 60+ parks and 4 tennis centers. Sounds impressive until you do the math. That's roughly 21 courts per 100,000 residents - falling 79% short of the USTA's target of 100 courts per 100,000 people. Most major metros average 15-25 public courts per 100,000 residents — roughly a quarter of the blended target. This target comes from the USTA's plan to have 350,000 courts serve 35 million players (10% of Americans) by 2035, assuming both public and private inventory. Most cities control only a slice of this, which is why public supply lags so badly. Dallas isn't alone - most major cities fall similarly short, but few have actively removed courts like Fair Oaks while populations grow.

It gets worse: Dallas has been removing courts, not adding them. On January 1, 2021, the city closed Fair Oaks Tennis Center entirely. Gone: 16 lighted courts from an already strained system. The reason? Budget cuts and flooding issues. The kicker? The city had just spent taxpayer money to resurface those courts before shutting them down.

Having managed both Samuel Grand and Fretz Tennis Centers for Dallas Parks and Recreation from 2008-2017, I watched these funding pressures build firsthand. City-run centers serve thousands on razor-thin budgets. When budget cuts come, tennis centers become easy targets because the broader community doesn't see them as essential infrastructure.

That's what numbers mean on the ground: a hub disappears, and so do a generation's reps.

These numbers aren't just statistics. For coaches like Curtis Reese, who had built programming at Fair Oaks, they meant watching a thriving tennis community disappear overnight. Reese captured the irony: "No one realized that the place was even open. It wouldn't take much effort to get the word out, and I know the community wants to utilize Fair Oaks."

Why Cities Don't Care

Here's the uncomfortable truth about why tennis infrastructure keeps disappearing: tennis doesn't show up when residents tell cities what they want.

Dallas conducts annual community surveys asking residents to list priorities. The 2024 results: infrastructure maintenance (61%), police services (44%), social services (27%). Roads and sidewalks topped the list at 57%.

Tennis courts? Not mentioned. Recreation facilities barely register compared to basic needs like fixing potholes, public safety, and helping homeless residents.

This explains why Dallas closed Fair Oaks and faced minimal political pushback. Tennis families noticed, but the broader community was focused elsewhere. When budget cuts came, tennis became an easy target.

The Land Economics Reality

Grant Chambers discovered this during six years trying to build RacFit in Austin. The problem isn't tennis courts - it's land.

As a current Austin resident, I see this land crunch daily. Austin's explosive growth made central land too valuable for tennis courts. Private developers generate exponentially more revenue per square foot with apartments than courts serving four people at a time. Grant's team got "pushed out" to Buda - a 20-minute drive that might as well be another planet for most junior players.

Dallas faces identical pressure. The city recently approved $345 million for parks - hundreds of millions in taxpayer dollars. But look closer at where it goes: playground replacements, recreation center upgrades, new trails. New tennis courts? Little to none. Land costs have made court construction nearly impossible.

What We're Actually Losing

Most tennis parents focus on finding good instruction and proper coaching credentials. But none of that matters if families can't get consistent court time.

Junior development requires repetition and routine. Kids need multiple sessions per week at predictable times that work with school schedules. When courts become unreliable - programs cancelled due to maintenance, families unable to book practice time - development stalls.

But there's something bigger at stake. Nobody goes to country clubs to learn tennis. They go there after they've learned tennis. Public facilities are where families discover the sport, develop basic skills, and figure out if tennis fits their lives.

When public tennis infrastructure disappears, tennis loses its primary entry point. Private facilities serve existing tennis families well, but they can't replicate the accessibility that introduces tennis to families who would never consider joining a club.

This creates a dangerous cycle: as public courts shrink, fewer families discover tennis. As the player base contracts, political support for tennis infrastructure weakens further.

[Note: This exact challenge is why I'm launching Tennis Parent Tuesday

next week - to help families navigate these complex decisions with

actual expertise, not guesswork.]

The Complete Pathway Problem

RacFit includes a foundation component because Grant understands that introducing kids to tennis creates responsibility. Simply exposing at-risk youth to the sport isn't enough. Without complete development pathways, these programs teach a devastating lesson: don't look beyond what you see outside your window because it isn't truly available to you.

This challenge drove my own Unfurrowed Ground Foundation's mission - ensuring every young person, regardless of background, had equal access to tennis benefits through public facility partnerships. The vision required what cities are now eliminating: reliable access to neighborhood courts where families could discover the sport.

This pathway requirement becomes more critical as technology disrupts traditional career paths. Tennis develops exactly the skills that remain valuable regardless of automation: leadership, time management, conflict resolution, sacrifice, grit.

Tennis teaches young people to manage competing priorities under pressure, resolve conflicts, make sacrifices for long-term goals, and persist through setbacks. These aren't just athletic skills - they're life skills that transfer to any field.

But developing these capabilities requires infrastructure that supports progression. From beginner facilities where kids try the sport, to intermediate programs where they develop skills, to competitive pathways where dedicated players pursue excellence.

When public courts disappear, this progression breaks. A child discovers tennis at a community program, shows interest and ability, then hits a wall when remaining options require expensive memberships their family can't afford.

The result isn't just lost tennis players - it's lost character development.

The Mission at Risk

This connects to something bigger: creating uncommon opportunities in common places. Tennis, traditionally viewed as elite, becomes accessible when quality programs exist in neighborhood parks and community centers. Public facilities transform what seems exclusive into something any family can try.

When cities close facilities like Fair Oaks or let courts crumble, they're not just removing recreational amenities. They're eliminating places where tennis stops being uncommon and starts being possible for regular families.

My Unfurroured Ground Foundation was built on this principle. The vision: every young person, regardless of background, would have equal access to tennis benefits. The mission required leasing courts at public facilities and providing instruction in disadvantaged areas and neighborhood parks.

None of that works when the infrastructure disappears.

The Innovation Nobody's Attempting

So the issue isn't whether cities can build sports infrastructure—it's whether tennis is framed to qualify.

But here's what makes this crisis particularly frustrating: proven models exist for building exactly the kind of tennis infrastructure we need. We just haven't figured out how to use them.

Living in Frisco from 2008-2020, I witnessed their transformation into "Sports City USA" firsthand. They mastered public-private sports facility partnerships better than any city in America. Since 2003, they've built five major sports venues: Riders Field for the RoughRiders, Comerica Center for the Dallas Stars, Toyota Stadium for FC Dallas, The Star for the Dallas Cowboys, and PGA Frisco for the PGA of America. Their recent $182 million Toyota Stadium renovation used multiple funding streams: $77 million from tax increment financing, $40 million from the Community Development Corporation, $65 million from private partners, plus additional performance-based incentives from their Economic Development Corporation.

In plain terms: they braided together city taxes, corporate partners, and development incentives to share risk while creating world-class facilities. The same model could build tennis facilities if we positioned them as community assets.

So how many public tennis courts does "Sports City USA" manage?

Six.

Four courts at Warren Sports Complex. Two courts at Shawnee Trail Sports Complex. That's it. The city that's spent hundreds of millions on sports venues through innovative public-private partnerships manages six tennis courts. They're even building 12 new pickleball courts at Warren Sports Complex with lighting and landscaping, while tennis gets the existing six courts and hopes for the best.

The misleading "over 100 public tennis courts" figure you see on Frisco's website includes school courts with severely restricted public access - locked during school hours, unavailable when teams practice, accessible only through a third-party system charging $11 per 90-minute session.

This reveals the real problem. It's not that cities don't know how to fund sports infrastructure. It's not that successful models don't exist. It's that tennis advocates haven't figured out how to position tennis facilities within the economic development frameworks that make other sports venues possible.

The Untapped Model

Frisco's Economic Development Corporation operates with clear metrics: job creation, capital investment, economic impact. In 2024, they facilitated 26 projects creating over 4,000 jobs and $1.5 billion in private investment. They use performance-based agreements - companies must meet specific targets before receiving incentives.

Tennis facilities, as typically proposed, don't meet those criteria. A soccer stadium hosts professional teams, major events, concerts, and generates ongoing economic activity. The Dallas Cowboys facility includes team headquarters, medical research centers, restaurants, retail, and luxury apartments. These create sustained employment and attract other businesses.

Tennis centers generate programming fees and court rentals.

But here's the innovation opportunity: Frisco's EDC recently launched programs that show willingness to fund projects serving broader community goals. They created an "investment zone pilot program" for downtown redevelopment with performance-based matching grants — basically, the city matches private dollars if the project proves it benefits the community. They appointed a Venture Capitalist in-Residence to support the local innovation ecosystem. These programs fund community development that happens to support economic goals.

A tennis facility positioned as youth development infrastructure, health and wellness programming, or community innovation showcase could potentially qualify for the same economic development funding that built Frisco's other sports venues. The key would be structuring proposals around measurable community benefits rather than tennis programming alone.

Youth programming serving underserved communities. Health and wellness classes addressing community fitness needs. Meeting spaces for non-profit events. Sports technology demonstration projects. Tennis becomes the delivery mechanism, not the mission.

Grant's RacFit model contains elements that could work within this framework: community-funded through local investors, focus on health and wellness programming, digital sports technology, family environment with gathering spaces, foundation component addressing at-risk youth development.

If positioned as workforce development programming (teaching life skills through tennis), health and wellness infrastructure (addressing community fitness needs), or innovation showcase (demonstrating sports technology applications), tennis facilities might qualify for the same economic development funding that built Frisco's other sports venues.

The Community Solution

The proven community model exists too. Grant's RacFit approach shows what works: 36 local investors putting up $25,000 each because they understood the need. When communities have skin in the game, facilities become gathering places worth protecting rather than budget items to cut.

Music playing, families gathering, kids using interactive technology alongside traditional courts. Tennis as community development, not country club exclusivity. The digital sports room with 13-foot interactive screens and 100+ games. Full indoor-outdoor bar and cafe creating social gathering space. Two indoor courts addressing the year-round programming challenge.

This community-centered approach creates the economic foundation that makes facilities sustainable while serving the broader population that cities care about. But it requires tennis advocates to stop asking for tennis facilities and start proposing community development projects that use tennis as the primary tool.

The barrier isn't lack of successful models - it's tennis advocates not understanding how to access them.

What Tennis Parents Must Do

After running city tennis facilities, living through a major city's sports infrastructure boom, and now experiencing Austin's court shortage crisis, one thing becomes clear: we need a completely different approach. Here's the three-step roadmap:

Step 1: Learn Your City's Development Language Read your EDC's last annual report; list 3 metrics they care about. Study your city's economic development corporation. What projects do they fund? What language do they use? Stop thinking like tennis parents and start thinking like civic advocates.

Step 2: Reframe Tennis as Community Infrastructure Draft a 2-sentence purpose statement for a "Youth Development & Wellness Center (with courts)." Stop saying "we need tennis courts" and start saying "we need youth development infrastructure that uses tennis to teach life skills." Position facilities as workforce development, health and wellness programming, and community gathering spaces that happen to include tennis courts.

Step 3: Engage Before Budget Decisions Are Made Email your council rep asking: "Which FY25 priorities fund youth programming and health outcomes?" Go to your city parks website and find when community surveys open. When bond elections include parks funding, dig deeper than court construction to understand their community development framework.

Most importantly, get involved before your kids need courts. By the time you're scrambling for court time, the crucial funding decisions have been made years earlier.

The Mission That Could Work

This connects back to the original vision: creating uncommon opportunities in common places. Tennis facilities positioned as community development infrastructure could access the same funding streams that built Frisco's sports empire.

But it requires abandoning the country club mindset that treats tennis as separate from community needs. Instead, tennis becomes the vehicle for addressing what cities actually care about: youth development, health outcomes, community gathering spaces, economic activity.

The infrastructure crisis threatens more than tennis development - it threatens the places where uncommon opportunities become possible in common places. But the solution exists. Cities have proven models for funding exactly what we need. Tennis advocates just need to learn how to use them.

Check your city's economic development strategy. Study their community development priorities. Learn their performance metrics. Then propose tennis infrastructure that delivers what they're already trying to achieve.

The future of tennis accessibility doesn't depend on cities changing their priorities. It depends on tennis advocates learning to align with the priorities cities already have.

Have questions about this topic? Join me live Tuesday September 30th

at 8 PM CST for Tennis Parent Tuesday where we can discuss this

in detail. Register at Tennis Parent Tuesday

Never Miss a Moment

Join the mailing list to ensure you stay up to date on all things real.

I hate SPAM too. I'll never sell your information.