The Third Bucket

Jan 28, 2026

Most tennis programs think they have a revenue problem. They have a structural problem that only shows up when development starts working.

The basic model looks simple enough. Families pay monthly tuition. Coaches get hired. Courts get scheduled. Tournaments get entered. As long as enrollment stays steady and checks clear, the program looks viable. From the outside, it functions. For a while, it usually does. The illusion holds when participation stays light and expectations stay low.

The system breaks when players get better. As improvement accelerates, costs curve upward in ways monthly tuition never accounted for. Travel expands from local to regional to national. Coaching density increases. Tournament schedules stretch across weeks and time zones. The time families commit rises alongside the money they spend. This is not a planning failure or an unexpected problem. This is what happens when development does exactly what it is supposed to do.

Most programs, though, build as if this moment will never arrive. They operate as if the tuition logic that works at entry level should sustain the system all the way through elite development. When reality shows up, they reach for the easiest tool available. They discount.

Scholarships appear quietly. Partial fees get negotiated behind closed doors. Temporary accommodations become permanent program features. The hope underneath all of it is that keeping higher-level players around at reduced cost will attract more full-paying families who want their kids near quality. Sometimes this works short term. More often, it delays a reckoning that arrives anyway.

Understanding why requires stopping the talk about pricing and starting the talk about buckets.

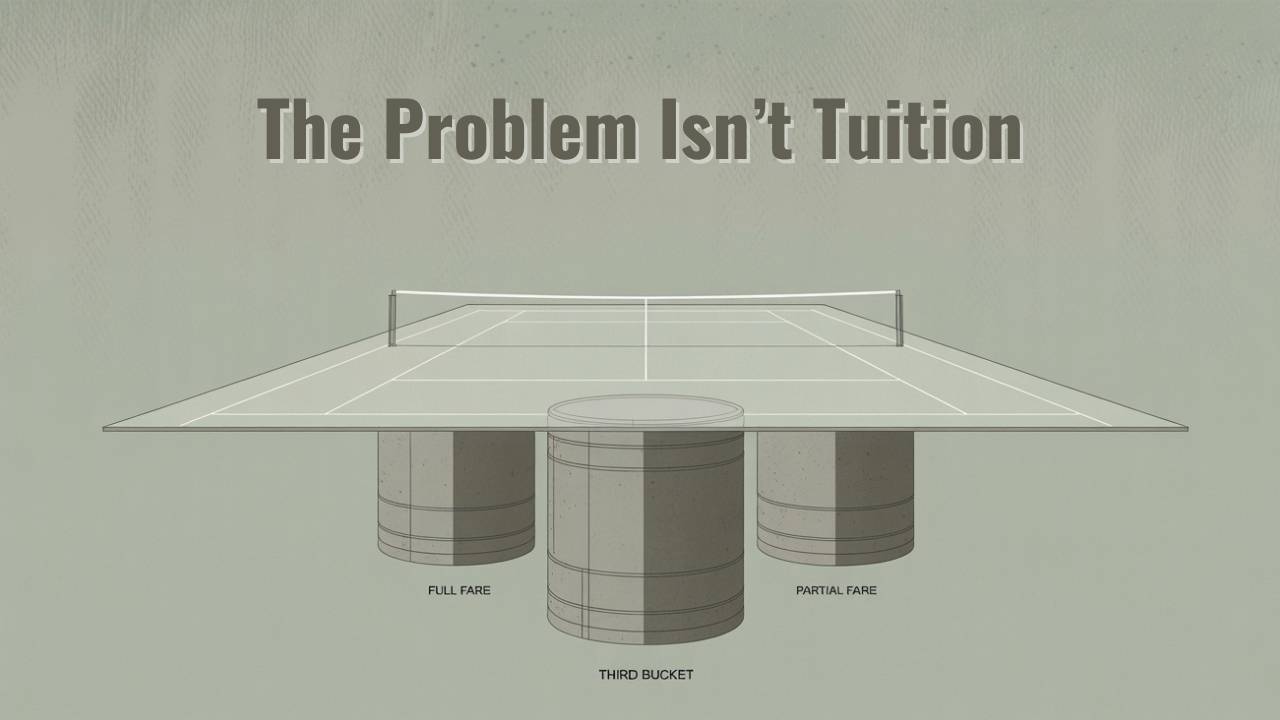

Every tennis program gets funded by some mix of three distinct economic roles, whether the program admits it or not. The first bucket holds full-fare families. These families pay posted rates without discounts or concessions. They generate margin. They stabilize cash flow. They subsidize everything else that happens in the program. No amount of talk about access or opportunity changes this. Without full-fare participants, the system collapses fast.

The second bucket holds partial-fare participants. These players pay enough to cover their marginal costs but not enough to generate profit. On paper, they look neutral. In practice, they serve a signal function. They raise the training environment's level. They validate the program's claims. They attract full-fare families who want their children around capable peers. Many programs call these players scholarship recipients, but economically they function closer to break-even assets than beneficiaries.

Most programs stop thinking there. They try balancing the system by adjusting the ratio between the first two buckets and assume growth solves the rest. That assumption is where the model breaks.

Without a third bucket, the economics never close.

The third bucket is externalized value. Money enters the system without tying directly to monthly participation. It takes different forms, but it shares one characteristic: it decouples revenue from court hours. This bucket absorbs costs that tuition cannot and should not carry.

Sometimes the third bucket appears as philanthropy. A nonprofit structure converts community goodwill into operating capital. Donations, grants, sponsorships, and fundraising events cover the real cost of scholarships, travel, staffing, and infrastructure. In these systems, financial aid is not a moral gesture. It is a budgeted line item supported by different logic than who can pay this month.

In other cases, particularly at elite development's sharp end, the third bucket looks like venture capital. Management companies support small groups of elite players knowing most will not return the investment. One might. If one does, management fees at the professional level justify losses elsewhere. This is not fairness. This is portfolio math applied to human development.

Less obvious third bucket forms exist too. Camps, clinics, events, consulting, coach education, media, and content licensing can all function as external revenue streams when they are not indexed to individual participation. Municipal support, school partnerships, and institutional subsidies can do the same. Patronage, though rarely named that way, still exists in many programs through individuals who underwrite costs because they value what the program represents rather than what it produces immediately.

What matters is not which form the third bucket takes. What matters is that it exists and gets deliberately designed.

When it does not, programs contort themselves quietly. Coaches get underpaid and told to be grateful. Discounts get granted selectively and explained poorly. Families sense something is off but cannot name it. Strong players drift away exactly when they should receive the most support. Burnout follows. Attrition accelerates. Everyone involved feels the pressure, but no one addresses the cause.

The pattern at the program level is consistent. Players enter as full-fare participants. As they improve, they become partial-fare cases justified by their environmental contribution. At the top end, a handful of players receive near-total cost reduction because they attract attention, validate the program, or hold out the possibility of future upside. Without a third bucket, those reductions get subsidized entirely by tuition, which means the first bucket carries a burden it never agreed to bear.

This is where resentment enters. Full-fare families start wondering why they pay more while others pay less. Discounted families feel indebted or precarious. Coaches manage emotional and ethical tensions that are actually structural. None of this happens by accident. This is the predictable outcome of asking one bucket to do the work of three.

The more honest question, then, is not whether a program should have a third bucket, but how that bucket should get used.

Two coherent answers exist, and every program lives somewhere between them whether it admits this or not.

One approach is concentration. The third bucket supports a small number of players at the upper echelon. Resources direct toward those most likely to produce exceptional outcomes. This is venture logic. It accepts that elite development is expensive, risky, and rare. It places asymmetric bets. If one player breaks through, the return justifies the investment. This model can work, but only when explicit. Everyone involved must understand that most will not be beneficiaries and that excellence, not equity, organizes the system.

The danger here is not unfairness. The danger is opacity. Programs that quietly run this model while marketing inclusivity inevitably fracture. Families feel misled. Players misunderstand their position. Coaches manage expectations that were never aligned with reality.

The other approach is distribution. The third bucket lowers costs across the board. Tuition gets reduced. Coaching density increases. Travel costs get absorbed. Facilities improve. The goal is not producing outliers but raising the baseline for everyone. This is cooperative logic. It values retention, stability, and long-term engagement. Attrition slows. Burnout decreases. The program feels like a place rather than a pipeline.

The risk here is not inefficiency. The risk is dilution. When resources spread too evenly without a clear developmental spine, excellence can flatten into comfort. Breakthroughs become rarer. The program becomes pleasant but unremarkable.

What does not work is pretending these two approaches can fully combine without consequence. A program cannot simultaneously claim egalitarian values and operate a hidden venture model. It cannot promise elite outcomes while distributing resources thinly and hoping talent self-selects upward. Those contradictions surface eventually, usually as quiet exits rather than public conflict.

The most durable programs are not the ones choosing the right answer. They are the ones choosing honestly.

Personal experience makes this clearer. When a program has a third bucket aligned with how the benefactor understands value, the system relaxes. In Charlotte, private patronage through the Carolina Youth Tennis Foundation stabilized staffing and logistics. Mike Schwarz's support meant a salary could get paid. Transportation could get provided. Planning became possible. The benefit did not confine itself to a few players. It flowed through the entire program by removing pressure from its most fragile points.

In Dallas, municipal support served a different function. The city understood that public tennis facilities were never meant to be fully self-sustaining under market logic. A modest stipend and the decision not to charge court fees for instructional hours acknowledged tennis as a public good. Instruction got treated as infrastructure rather than a revenue opportunity. The third bucket did not chase excellence. It ensured baseline viability.

These examples matter because they show third buckets do not need to be heroic. They do not need to be glamorous. They simply need to align with purpose. When they do, programs behave coherently. When they do not, systems compensate until they break.

The deeper lesson is that the third bucket is where values become operational. It is where a program stops talking about what it believes and starts funding it. Once that decision gets made consciously, the rest of the business model becomes easier, not harder. The system stops arguing with itself.

Junior tennis does not suffer from lack of passion. It suffers from lack of structural honesty. Programs keep redesigning schedules and curriculum while ignoring the economic architecture that determines whether any of it can last. Until the third bucket gets named, designed, and aligned with purpose, development will continue to falter not on court, but underneath it.

The uncomfortable truth is that most programs fail not because they lack expertise, but because they never decided what kind of system they were actually trying to build.

Never Miss a Moment

Join the mailing list to ensure you stay up to date on all things real.

I hate SPAM too. I'll never sell your information.