What Bronson Alcott Knew That Horace Mann Couldn't Scale

Jan 19, 2026

Calibration Series - Essay 2

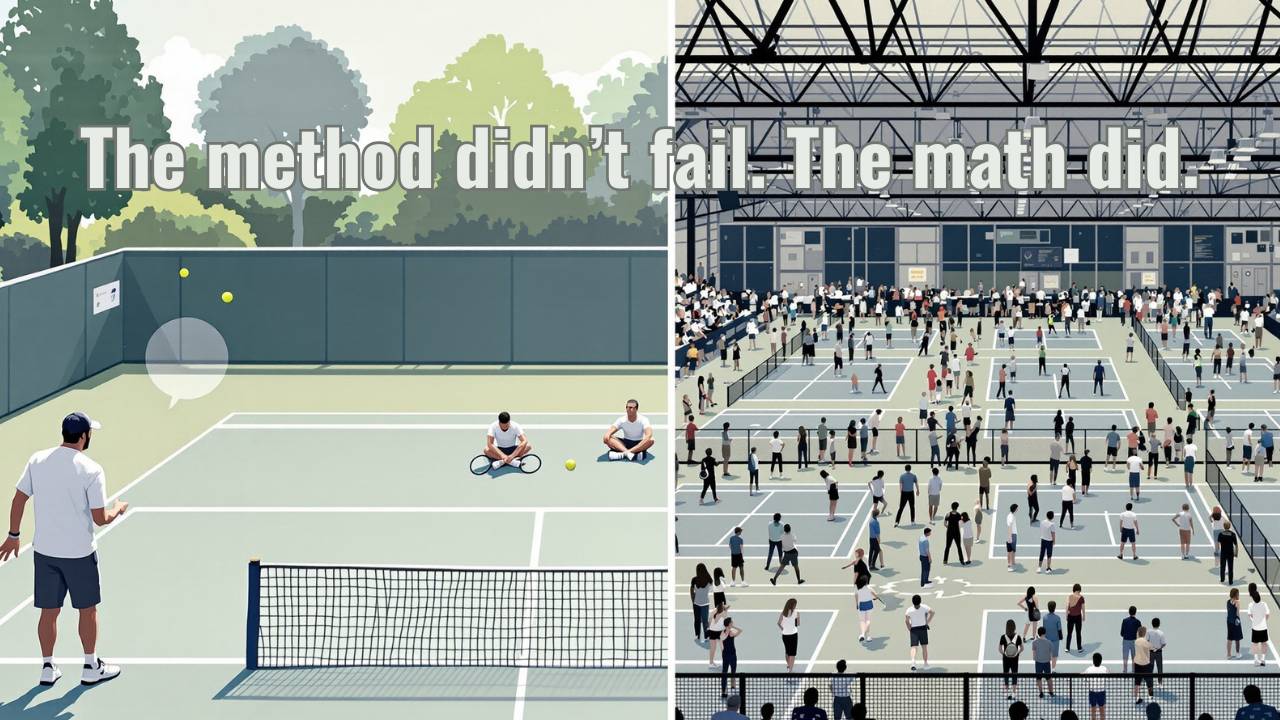

Your child's tennis coach knows your kid needs different instruction than the player on the next court. Watches them struggle with the same tactical concept three other players picked up easily. Sees the confusion in their face when everyone else nods along. But the coach has thirty-seven other students, a curriculum to cover, and a schedule to maintain. So the instruction stays the same. And your child keeps falling further behind.

This is not a coaching problem. This is a mathematics problem that has existed for 190 years.

In 1834, a schoolteacher in Boston did something that seemed simple. He watched children closely. He asked them questions. He listened to their answers. Then he adjusted his teaching based on what he heard. Not what he expected to hear. What he actually heard.

Bronson Alcott's Temple School became famous because his students learned faster than anyone thought possible. They understood concepts that children their age supposedly could not grasp. They asked questions that revealed genuine thinking rather than rote repetition. Parents came from across New England to see what was happening.

What was happening was observation. Systematic, individual, responsive observation. The same thing your child's coach wishes they could do but cannot maintain across forty students.

Alcott did not assume what a child understood. He watched until he could see it. He did not guess where confusion lived. He asked questions until the child revealed it. He did not impose standardized lessons. He adapted to what each child actually needed in that moment.

This worked perfectly. For about thirty children. With one teacher. Who had the time, skill, and temperament to maintain that level of attention.

Then Horace Mann tried to scale it. And discovered the same constraint your child's tennis academy hits every season.

The Method That Worked (And Still Does, For Six Students)

Walk into any elite tennis training session with six or fewer players. Watch what happens. The coach sees exactly what each player needs in real time. Notices when one player processes tactical patterns visually while another needs to feel the movement first. Adjusts explanations mid-sentence based on which kid is nodding and which one looks lost. Remembers that this player struggled with the same concept three weeks ago and needs a different entry point.

This is Alcott's method. Individual observation. Responsive adjustment. It works perfectly at this scale.

The only way to know what a child actually understands is to observe that specific child. Watch their face when you explain something. Notice where their attention shifts. Ask a question and listen to how they construct the answer. Not whether the answer is right. How they arrived at it.

This takes time. It requires full attention. You cannot do it while managing thirty other students. You cannot do it while following a standardized curriculum. You cannot do it if your job depends on moving everyone through the same material at the same pace.

The coach who trains six players can maintain this. The coach who trains forty cannot. Not because of skill. Because of mathematics.

The System That Could Not (And Your Academy Cannot Either)

Horace Mann faced a different problem. Massachusetts had thousands of children who needed education. Most families could not afford private schools with six-student classes. Most communities could not hire teachers trained in Alcott's methods. The state needed a system that worked at scale, with average teachers, serving diverse students, within limited budgets.

Your child's tennis academy faces the exact same constraint. Parents want affordable training. Coaches need to earn sustainable income. Facilities need full courts with multiple sessions running simultaneously to stay viable. The math forces standardization even when everyone knows individual attention works better.

Mann's solution was standardization. Create a curriculum that works for most children. Train teachers to deliver it consistently. Organize students by age so they move through material together. Measure progress through testing that does not require individual observation.

Sound familiar? Your academy groups players by age and NTRP level. Uses a curriculum designed for "the average 12-year-old 4.0 player." Measures progress through tournament results that do not reveal why your child is losing. The coach delivers the same tactical session to eight players who process information eight different ways.

This is not laziness. It is mathematics. You cannot hire enough coaches to observe every child individually. You cannot pay coaches enough to maintain that level of attention across thirty students simultaneously. You cannot design a system where every lesson adapts to every child's specific processing style.

So academies build infrastructure that assumes calibration. The curriculum assumes players at each level need similar instruction. The group training assumes standard delivery will work for most students. The tournament results assume wins and losses indicate genuine understanding of tactics.

When the system works, it works well. Students who fit the standard profile develop efficiently. But when the system does not work, it fails invisibly. Your child who processes evidence-based reasoning gets pattern-based instruction and looks lost. The player who needs spatial visualization gets verbal explanation and cannot execute under pressure. The system keeps moving forward because it cannot stop to observe what individual children actually need.

This is why your investment is not producing the results you expected. Not because your child lacks ability. Not because the coach lacks expertise. Because human attention does not scale past a certain point without infrastructure support.

The 190-Year Constraint (That Explains Your Last Three Coaches)

For nearly two centuries, every attempt to individualize education hit the same wall. Individual observation works. Standardized systems scale. But individual observation does not scale through human labor alone.

You have probably seen this play out already. Your child worked with a private coach. Just the two of them. Progress was incredible. The coach saw exactly what your kid needed. Adjusted in real time. Your child's game transformed.

Then you moved to group training because private lessons were not sustainable. Or the private coach took on more students to build their business. Suddenly the instruction that was so precise became generic. Your child started falling through the cracks. Not because the coach stopped caring. Because human attention has limits.

Reformers tried smaller class sizes. Still too many students per teacher to maintain real calibration. They tried ability grouping. Created new categories but same problem within each group. They tried differentiated instruction. Required teachers to design multiple lesson versions while managing thirty students in real time.

Every solution assumed the same constraint. Coaches are human. Humans can only observe so much simultaneously. Humans cannot cross-reference multiple perspectives instantly. Humans cannot remember every detail of every student's learning pattern across weeks and months while also delivering instruction, managing court rotations, meeting curriculum requirements, and handling parent communications.

The constraint was not coach quality. It was human cognitive capacity. Alcott's method required more processing power than any human possessed at scale.

This is why switching coaches rarely fixes the problem. The new coach has the same cognitive limits as the last one. Better expertise does not solve the mathematics of attention at scale.

What Actually Changes (For Your Child's Coach)

This is where most discussions about education technology go wrong. They assume technology replaces teachers. It does not. Technology removes the cognitive load constraint that prevented coaches from doing what Alcott did.

Think about what your child's coach already knows but cannot act on. They know your kid processes tactics differently than the player next to them. They notice which explanations land and which create confusion. They remember that three weeks ago your child struggled with the same concept. They see the pattern.

But they cannot act on all of this simultaneously while coaching forty students, running drills, managing court rotations, watching technique, correcting positioning, monitoring effort levels, and handling questions from eight different players at once. So the insight sits unused. And your child keeps receiving instruction that does not match how their brain actually works.

The infrastructure to remove this constraint now exists. Not through automation. Through augmentation. The coach still designs the training session. Still builds relationships. Still makes judgment calls about when to push and when to step back. But the coach now operates with observation capacity that was previously impossible at scale.

How it works matters less than understanding why it matters. The constraint was real. The constraint shaped everything. And the constraint has changed.

Why This Matters For Your Investment

You have probably spent thousands of dollars on tennis training by now. Private lessons. Group clinics. Tournament fees. Travel. Equipment. The investment keeps growing but the results plateaued months ago.

The problem is rarely the amount of training. It is whether the training matches how your child's brain actually processes information under pressure.

Tennis makes calibration failures visible quickly. A player either executes under pressure or does not. Either understands tactical patterns or gets confused. Either processes coaching in real time or looks lost during matches. There is nowhere to hide.

When I work with families, I am doing what Alcott did. Watching the player closely. Listening to what the coach says and how the player hears it. Observing what you as the parent intend and what your child experiences. Then translating across all three perspectives so communication actually lands.

This works. But it does not scale. I can maintain calibration with maybe six families at once if I am fully engaged. Past that, quality degrades. Details blur. I start relying on patterns instead of seeing what is actually in front of me.

The Player Development Plan system we built with partner academies solves this. Not by replacing coaches. By giving coaches the ability to maintain calibration across forty players when they could previously manage six. Same expertise. Same judgment. Just freed from the cognitive load that made systematic observation impossible at scale.

This is what you are paying for when you invest in systematic player development. Not more hours of training. Better calibration during the hours you are already investing in.

The Infrastructure That Did Not Exist (Until Now)

When Alcott built his school, the technology to scale his method did not exist. Mann built systems that worked within available technology. Those systems served millions of students. They were the right solution for the constraints that existed.

Your child's academy operates the same way. Group training. Age-based groupings. Standardized curriculum. These are rational choices given that human coaches have cognitive limits. The academy is doing the best it can within the constraints that exist.

But the constraint has changed. We now have infrastructure that can observe systematically, cross-reference perspectives automatically, and identify patterns that humans miss. Not because the technology is smarter. Because it does not fatigue. It does not forget. It processes more simultaneously than human attention allows.

Individual observation no longer hits the scaling wall. The coach who could previously maintain deep observation with six students can now maintain it with forty. Alcott's method no longer requires choosing between depth and reach.

This is not someday technology. This is what we have built and tested with partner academies. Not through AI replacing coaches. Through infrastructure removing the cognitive load constraint that forced the choice between seeing clearly and serving many.

What This Means For Your Next Decision

Alcott was not wrong. His method worked. Mann was not wrong either. His system was the best solution available given existing constraints. They were both right. They were both solving for different variables within the technology landscape they inherited.

Your child's current coach is not wrong. Group training is not wrong. The academy's curriculum is not wrong. They are all working within constraints that have existed for 190 years.

What failed was not vision. What failed was infrastructure. The infrastructure to make individual observation scale did not exist. So we built systems that worked without it. Those systems accomplished tremendous things. They also left damage in their wake.

The work ahead is not replacing one system with another. It is completing what Alcott started and Mann tried to scale but could not because the technology was not ready.

The question now is not whether this is possible. The question is whether you want your child's development to continue operating under the old constraint or to benefit from infrastructure that removes it.

Questions That Actually Matter:

How many times have you watched your child receive instruction that you could tell was not landing, but the coach kept moving forward because there were thirty other students waiting?

If your child's coach could maintain the same level of individual attention they give to six students across all forty students in the program, what would change in your child's development?

What would it be worth to you to know that every hour of training your child receives is calibrated to how their brain actually processes information under pressure instead of hoping they adapt to generic instruction?

Never Miss a Moment

Join the mailing list to ensure you stay up to date on all things real.

I hate SPAM too. I'll never sell your information.